IMAGE CREDIT: CHATGPT

If you have been feeling like it’s getting hotter each year in Africa, you’re not wrong.

A new scientific study has confirmed what you and many people across Africa may be feeling in their bones: human-driven climate change is turning up the heat.

Published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, the study has found that greenhouse gases from human sources are making African heatwaves worse.

These gases–such as carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels–are trapping heat in the atmosphere, raising temperatures, and pushing the climate into unfamiliar territory.

The researchers studied weather data from 1950 to 2014 to understand how heatwaves have changed and what’s causing the changes. Their conclusion is: heatwaves across Africa are getting worse, and it’s happening mostly because of human-caused climate change.

But first, what exactly is a heatwave? In simple terms, it’s a stretch of unusually hot weather that lasts for at least three days. These can be daytime heatwaves–when daytime temperatures are too high–or nighttime heatwaves, when the nights don’t cool down. There are also compound heatwaves, where both day and night temperatures stay abnormally high. These are especially dangerous because they give people, animals, and even the land itself no time to recover from the heat.

Two time periods

The study divides recent African climate history into two key periods. The first, from 1950 to 1979, was relatively stable in terms of temperature trends. During this time, although greenhouse gases were increasing, another factor was helping to keep things cooler: aerosols. These are tiny particles from air pollution–like smoke and industrial emissions–that float in the atmosphere and reflect sunlight.

These particles acted like a kind of “shield,” bouncing some of the sun’s energy away from Earth. As a result, while greenhouse gases were slowly warming the planet, aerosols were cooling it down, and the two effects largely balanced each other out. That’s why heatwaves during this earlier period were not getting significantly worse.

However, this balance changed in the 1980s. Many countries, especially in the industrialized world, began to clean up their air by cutting down on pollution. Aerosol levels dropped. But greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise, especially from cars, factories, power plants, and deforestation. Without the cooling effect of aerosols to hold it back, the warming effect of greenhouse gases took over. From 1985 to 2014, the researchers observed a sharp and steady increase in heatwaves across Africa.

One particularly worrying trend is the rise in nighttime heatwaves. These are dangerous because they rob people of the chance to cool down after a hot day. When the night stays hot, the body doesn’t get a break, and this increases the risk of heat-related illnesses such as heatstroke, dehydration, and even death. Vulnerable groups like the elderly, children, and people with health conditions are especially at risk. The researchers found that nighttime heatwaves are increasing even faster than daytime ones, and this is already affecting health and quality of life across the continent.

The scientists behind the study also wanted to know what’s causing all this. Is it just natural climate fluctuations, or is human activity the main driver? To answer this, they used advanced computer models to separate natural climate variability from human-caused changes.

Their results show that before 1980, natural changes in the climate explained about 80% of heatwave trends. But after 1985, the influence of natural variability dropped to about 30%. In other words, most of the recent increases in African heatwaves are being driven by human activities.

The study also looked at the physical processes behind the warming. Rising greenhouse gas levels were found to increase the amount of heat-trapping radiation near Earth’s surface, especially at night. At the same time, reductions in cloud cover–caused by fewer aerosols–let more sunlight reach the ground.

On top of that, drier soil and reduced vegetation in some areas meant that less water was evaporating to cool the land, making heatwaves even more intense. Finally, changes in wind and air pressure systems were trapping hot air over certain regions, making heatwaves longer and more severe.

These changes are not just a problem for the weather–they are already creating serious challenges for people across Africa. Heatwaves threaten agriculture by drying out crops and reducing yields. They increase demand for electricity as more people turn to fans and air conditioners–if they have access to them. They stress hospitals and public health systems. And they hit the poorest communities hardest, especially in crowded urban areas where homes are poorly ventilated and shade is limited.

The researchers warn that if current trends continue, the consequences could be severe. For instance, in Nigeria, heat-related deaths could rise from around 9,000 per year today to as many as 43,000 annually by the end of this century. The study emphasizes the urgent need for action–not only to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also to help African communities adapt to the heat.

Solutions include better early warning systems for extreme heat, more public education about how to stay safe during heatwaves, and smarter urban planning to create cooler, more livable cities. Buildings can be designed to stay cooler without air conditioning, and green spaces can help lower temperatures in city neighborhoods.

But above all, reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is essential to stop the worst effects of climate change from taking hold.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

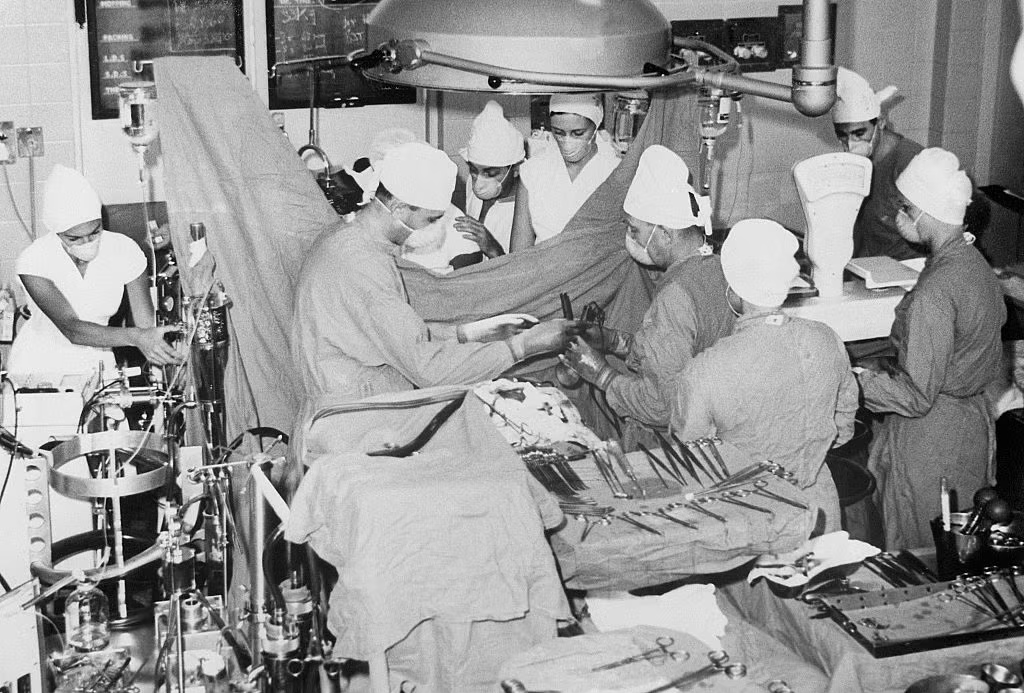

Did you know? The first human heart transplant in the world was performed in Africa, specifically at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, on December 3, 1967. Read about this operation.

QOUTE OF THE WEEK

“This surge is no coincidence…prolonged rains have fuelled mosquito breeding, while activities like gold panning, fishing and artisanal mining are exposing more individuals to risk, especially during peak mosquito activity hours” Dr. Memory Mapfumo, an epidemiologist at the Africa CDC on malaria surge in Southern Africa.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Origin of North Africans: A study which analyzed over 700 ancient and modern maternal DNA samples from North Africa found that the region’s people have roots from three main sources: Eurasia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and a distinct North African lineage. These ancestral influences arrived in multiple waves over tens of thousands of years. One key movement happened during the “Green Sahara” period, when the desert was green and allowed human migration from the south. Later, people came from Europe, the Middle East, and around the Mediterranean.

Today, most North Africans carry Eurasian ancestry, but traces of ancient North African and sub-Saharan maternal lines remain. The research highlights North Africa’s long-standing role as a meeting point of human migrations. [Reference, Scientific Reports]

Heatwaves Worsen Child Hunger: A study which examined 36 countries, including many in Africa, found that heatwaves make it harder for mothers to feed young children properly. In sub-Saharan Africa, over 90% of children already don’t get the minimum acceptable diet, and heat makes things worse. During heatwaves, children were less likely to eat enough, be fed often, or get healthy foods like vegetables, fruits, and beans. Poor families in rural areas, especially those without fridges or fans, were hit hardest.

The study showed these feeding problems can last up to two weeks after the heatwave. As Africa faces more frequent extreme heat due to climate change, the researchers urge governments to include emergency heat responses in child nutrition programs to protect children’s health. [Reference, The Lancet Planetary Health]

Community Initiatives Can Reduce Open Defecation: A study which looked at the impact of a government project called Community-Led Total Sanitation found that it helped reduce the number of people in Uganda who defecate in the open. Using national survey data from 2016, researchers compared areas where programme was implemented with areas where it was not.

After matching similar districts for fair comparison, they found that programme reduced open defecation by 37%. The study also revealed that poorer, rural, and less-educated households are more likely to practice open defecation. Cultural beliefs and poverty were major barriers. The researchers recommend that Uganda expand CLTS to more districts to help reach its goal of ending open defecation by 2025. [Reference, PLOS One]