IMAGE CREDIT: CHATGPT

Step into Lagos, Cairo, or Kinshasa, and you’ll find bustling streets, new high-rises, and a wave of opportunity as millions move into Africa’s expanding cities. But along with this growth comes a less visible threat: the very air people breathe.

According to a perspective published in Global Challenges, air pollution is now responsible for more than 1.1 million deaths across the continent every year, more than malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis combined.

What makes the crisis worse is that much of it goes unseen. Fine particulate matter–tiny particles known as PM2.5 that come from cars, factories, open burning, and even household cooking fires–slips deep into the lungs and bloodstream. Once inside, they trigger asthma, heart disease, lung cancer, and deadly pneumonia in children. Researchers warn that unless African countries act fast, the toll could rise dramatically as cities expand.

A perfect storm of growth and pollution

Africa is urbanizing faster than any other region in the world. By the end of the century, 13 of the world’s 20 largest megacities will be African, with Lagos, Kinshasa, and Cairo already bursting at the seams. This rapid growth has brought opportunity, but it also means more cars, more factories, and more pressure on already fragile infrastructure.

“The burden is shifting,” the paper notes. Until recently, two-thirds of Africa’s air pollution deaths came from household smoke–families burning wood, charcoal, and kerosene to cook and light their homes. But as cities expand and industrialize, outdoor or “ambient” air pollution from vehicles, industry, and waste burning is catching up fast.

The engines of dirty air

The study points to five main culprits behind the rising pollution levels in Africa’s cities:

. Urbanization: As millions flock to cities, demand for transport, housing, and energy soars, straining services and worsening emissions.

. Industrialization: From oil refineries in Nigeria to steel plants in South Africa, poorly regulated industries pump sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and fine particles into the atmosphere.

. Transportation: Africa imports nearly 40% of the world’s second-hand cars. Many are old diesel models that spew toxic fumes. Road dust, motorcycle taxis, and chronic traffic jams—Lagos tops the world with a 70-minute average delay—add to the smog.

. Household energy: Despite growing cities, many families still rely on charcoal and kerosene. In homes in Nigeria, PM2.5 levels have been recorded at 1,000 micrograms per cubic meter—200 times above World Health Organization (WHO) safe limits.

. Open burning: Across the continent, fields and trash piles are set ablaze, releasing clouds of smoke filled with hazardous chemicals. Cities like Abidjan and Lagos are regularly blanketed by this seasonal haze.

Together, these factors make African megacities some of the most polluted in the world.

Blind to the problem

One of the paper’s most troubling findings is that African cities often don’t even know how bad the air really is. Monitoring systems are scarce, expensive, and unreliable. In many capitals, the only consistent data comes from sensors at U.S. embassies–devices meant to protect diplomats, not track national health.

But these monitors are often placed in leafy compounds, meaning the readings may actually underestimate real pollution levels. Other methods, such as using airport visibility data or satellite estimates, are patchy and sometimes misleading.

This lack of reliable data makes it hard for governments to set strong policies–or even to convince the public of the urgency of the problem. As the authors write, the result is “fragmented efforts” where air pollution often takes a back seat to more visible crises like housing shortages or food security.

A Threat to Development

The economic costs of inaction are staggering. By 2040, cities like Accra, Lagos, and Nairobi could lose nearly $140 billion due to pollution-related health problems and lost productivity. At the same time, dirty air threatens Africa’s ability to meet global Sustainable Development Goals, from clean energy to healthy cities.

Yet solutions exist. In Beijing, for example, a “Clean Air Action Plan” between 2013 and 2017 slashed pollution by up to 68% through strict vehicle standards, coal bans, and limits on factory emissions. Similar approaches, adapted to Africa’s realities, could save lives and boost economies.

What Needs to Change

The researchers call for a “multi-stakeholder, bottom-up approach” to tackle the crisis. That means stronger monitoring networks like Uganda’s AirQo project, stricter rules on industrial emissions and vehicle imports, and a rapid transition toward clean energy for homes and businesses.

Robust action is needed. As the authors warn, “Failing to act will prolong poor air quality conditions in the continent while worsening global environmental health inequalities.”

For the millions of people already living in these crowded cities, the fight for clean air is not just about the environment, it’s about survival.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

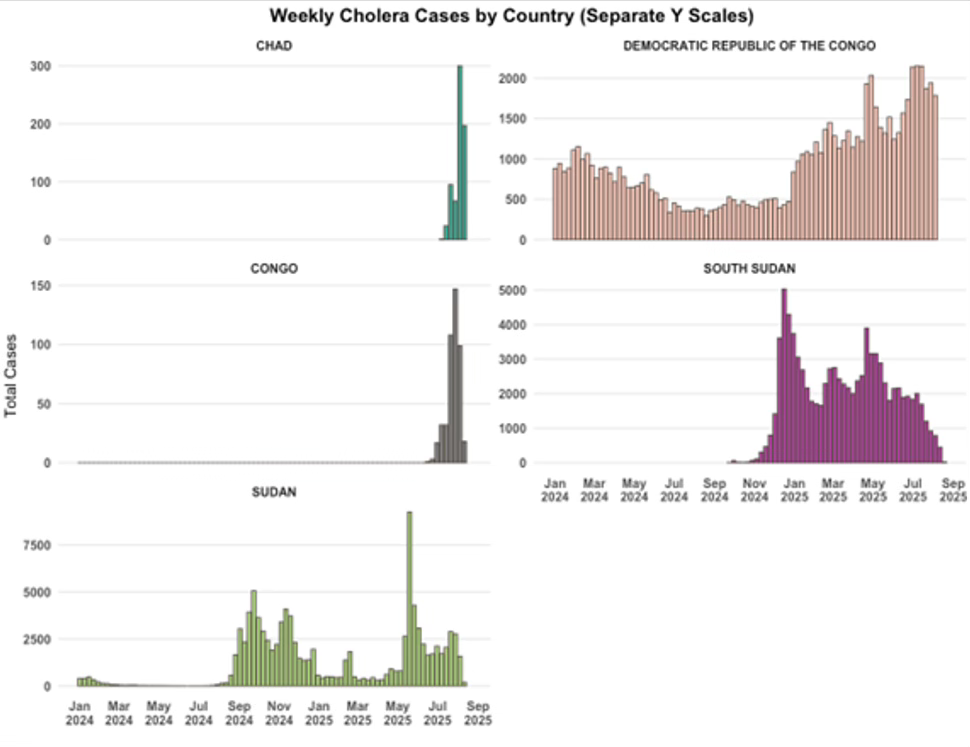

Countries such as Chad, the Republic of the Congo, the DRC, South Sudan, and Sudan have reported some of the worst cholera outbreaks in Africa, according to data available as of 17 August 2025. Credit: WHO. Read a WHO report.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“No matter where people live and no matter how active they are, it’s what they eat that appears to drive obesity…” new study reveals.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Climate Change to Reshape Africa’s Food Security: climate change will reshape Africa’s food security, with sharp contrasts across staple crops. Using machine learning and climate models, researchers project that maize–the region’s dominant staple–will suffer steep yield losses, especially in South Africa and Zambia under high-emission scenarios. By contrast, rice and wheat are likely to benefit from rising carbon dioxide, with yields surging in West Africa, Nigeria, and South Africa. Soybeans, though more stable, may experience slight declines despite their nitrogen-fixing advantage.

The findings highlight a stark divide: while some regions could see yield gains of over 50%, others face crippling declines. The study urges targeted adaptation–such as resilient crop varieties and irrigation investments–to avert deepening hunger in Sub-Saharan Africa. [Reference, Scientific Reports]

When Elephants Vanish, Ebony Trees Falter: a team of scientists has uncovered a surprising connection between elephants and ebony trees in Central Africa. The study shows that forest elephants, hunted nearly to extinction for their ivory, are also vital to the survival of ebony. Elephants eat the trees’ large fruits and deposit the seeds in their dung, which protects them from rodents and helps them sprout. In areas where elephants have vanished, young ebony trees are scarce — with sapling numbers dropping by more than two-thirds. [Reference, Science Advances]

Heatwaves Threaten Child Nutrition in Africa: As heatwaves intensify across Africa, new research reveals they are undermining how babies and toddlers are fed. The study, covering 36 low and middle-income countries, found that extreme heat makes it harder for children under two to get enough meals or a balanced diet. In sub-Saharan Africa, where over 90% of children already miss minimum diet standards, heatwaves worsen the crisis–reducing food diversity and cutting access to vital fruits, vegetables, and legumes.

Rural families, poorer households, and those without fridges or cooling are hit hardest, with feeding disruptions lasting up to two weeks after the heat ends. Experts warn that unless nutrition programmes include heat-adaptation strategies, Africa’s youngest children risk long-term harm to their growth and development. [Reference, Lancet Planetary Health]

—END—