For years, Africa’s forests have quietly helped protect the planet. They pulled huge amounts of carbon dioxide out of the air, storing it in trees and vegetation. Scientists call this a carbon sink, and it’s one of nature’s most important tools for slowing climate change.

But a new study in Scientific Reports, in which researchers used advanced satellites and machine-learning techniques, has discovered something troubling: Africa’s forests have stopped acting as a carbon sink. Instead, they are now releasing more carbon than they absorb.

In other words, the forests that once helped cool the planet are now doing the opposite.

The research team built the most detailed maps ever made of Africa’s forest biomass. Biomass refers to the amount of wood and vegetation above the ground, an easy way to measure how much carbon is stored in forests. The scientists used laser-based satellites and radar data to measure forest height and density across millions of hectares.

They then compared how much biomass the continent gained or lost over 10 years.

Here’s what they found:

. 2007–2010: Africa gained a huge amount of biomass each year, about 439 million tonnes. Forests were thriving and storing more carbon than they released.

. 2010–2015: The trend flipped. Africa lost around 132 million tonnes of biomass per year.

. 2015–2017: The losses continued at around 41 million tonnes per year.

This shift is significant. It marks the point where Africa’s forests went from helping fight climate change to contributing to the problem.

What went wrong?

The biggest reason for this change is deforestation.

Africa’s tropical moist broadleaf forests–the huge, lush rainforests of Central and West Africa–are packed with carbon. But they are also under intense pressure from farming, logging, charcoal production, mining, and population growth.

Countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, and several West African nations have seen major increases in forest loss over the past decade. When these forests are cut down or burned, all the carbon stored in their trees goes straight into the atmosphere.

The losses are so large that they overwhelm gains happening in other parts of the continent.

Savannas growing but not a big deal

Interestingly, some African savannas–those grassy landscapes scattered with trees–are gaining biomass. Scientists think this may be because higher levels of carbon dioxide in the air help shrubs and trees grow faster, slowly changing the balance between grassland and woodland.

But these gains, while important, are nowhere near enough to make up for the massive losses in the dense tropical rainforests. Losing a single hectare of rainforest can release more carbon than several hectares of savanna can absorb.

Why it matters for the world

Africa plays a much bigger role in the global carbon cycle than many people realize. The continent contains about 20% of the world’s forest-based carbon and drives around 40% of global biomass-burning emissions. When Africa’s forests struggle, the whole world feels it.

Because these forests have now become a carbon source instead of a sink, it widens the gap between where global emissions are today and where they need to be. This makes meeting the Paris Agreement climate targets much harder.

Can this be reversed? Ye. But it will take urgent action.

The scientists behind the study say Africa needs stronger forest protection, better governance, and better tools to detect and stop illegal logging.Restoring damaged forests, protecting existing ones and reducing the economic pressures that drive deforestation will be key.

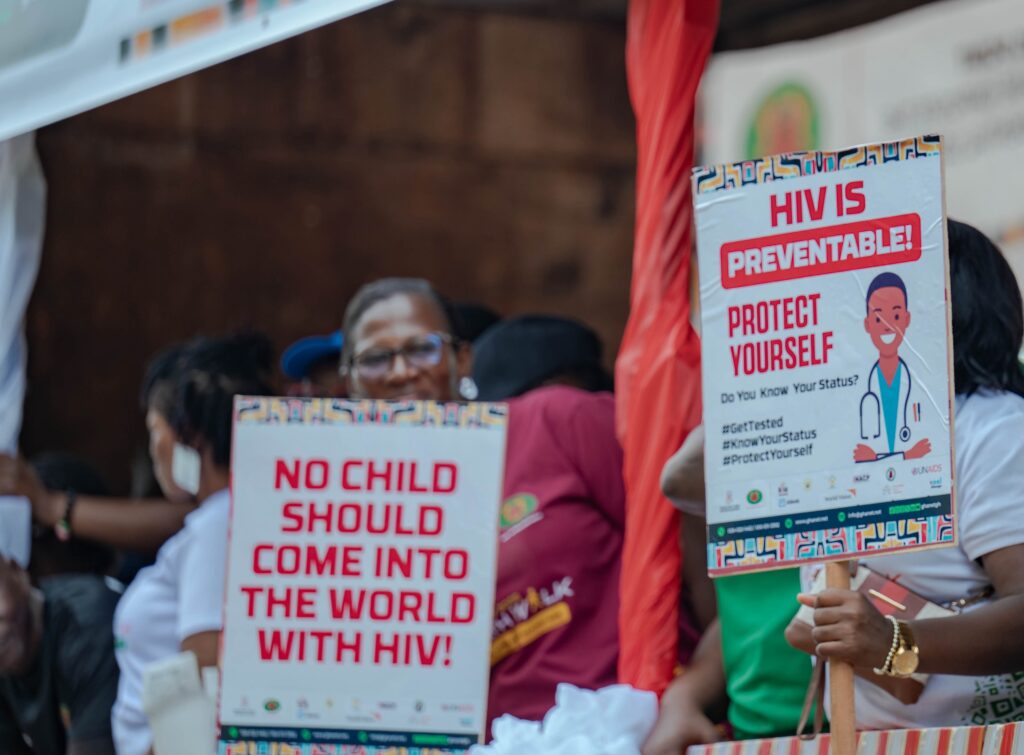

PHOTO OF THE WEEK

Today is World AIDS Day 2025, marked under the theme “Overcoming Disruption, Transforming the AIDS Response,” a call to push past recent challenges and rebuild a stronger, more resilient global fight against HIV. Photo Credit: WHO Africa

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“Armed conflict in Sudan has severely disrupted healthcare access, leaving more than half of patients unable to obtain essential medications,” Ali Awadallah Saeed, and colleagues, PLOS Global Health

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Africa’s silent heat crisis intensifies: Sub-Saharan Africa is becoming more vulnerable to deadly heatwaves, a new study of more than 50,000 deaths shows. Unlike wealthier countries, where people are slowly adapting to rising temperatures, African communities are facing worsening risks, especially from hot nights, when the body should cool down. Nighttime heat-related deaths rose sharply between 2005 and 2015, and combined day-night heatwaves also became significantly more dangerous.

Men, young children, and the elderly were hit hardest, with older adults showing the biggest jump in nighttime mortality. Researchers say limited access to cooling, unreliable electricity, and poor housing are major drivers. They warn that Africa urgently needs heat-alert systems and low-cost, locally tailored cooling solutions to prevent rising loss of life. [Reference, Science Advances]

AI model maps drought without needing ground data: A new study introduces an AI system that can map drought in the Horn of Africa without relying on scarce on-the-ground weather data. The model, called SAED-ViT, learns patterns directly from 25 years of satellite observations–tracking vegetation health, land temperature, and rainfall. It detects drought by spotting unusual seasonal shifts, then groups them into clear categories like “severe” or “extreme” using unsupervised learning, meaning no human-labeled data is required.

The system successfully identified major drought years such as 2011, 2017, and 2022 and matched closely with the widely used drought index, performing better than traditional vegetation-based indicators. Researchers say it offers a fast, scalable tool for early warning in one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions. [Reference, Earth and Space Science]

Climate change gives malaria mosquitoes the upper hand. Warming temperatures are making Africa an even friendlier home for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Researchers tested two major species–Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis–under different temperature conditions. They found that both species survived and reproduced far better in warmer climates, with A. arabiensis showing a particularly strong boost as temperatures rose.

Using these lab results, the team projected future climate impacts and discovered that the areas most suitable for these mosquitoes will expand across East Africa by 2050. This means regions that previously saw little malaria could face growing risk. The authors say climate change will likely strengthen malaria transmission unless countries act quickly to improve surveillance, mosquito control, and public-health preparedness. [Reference, Global Change Biology]

—END—