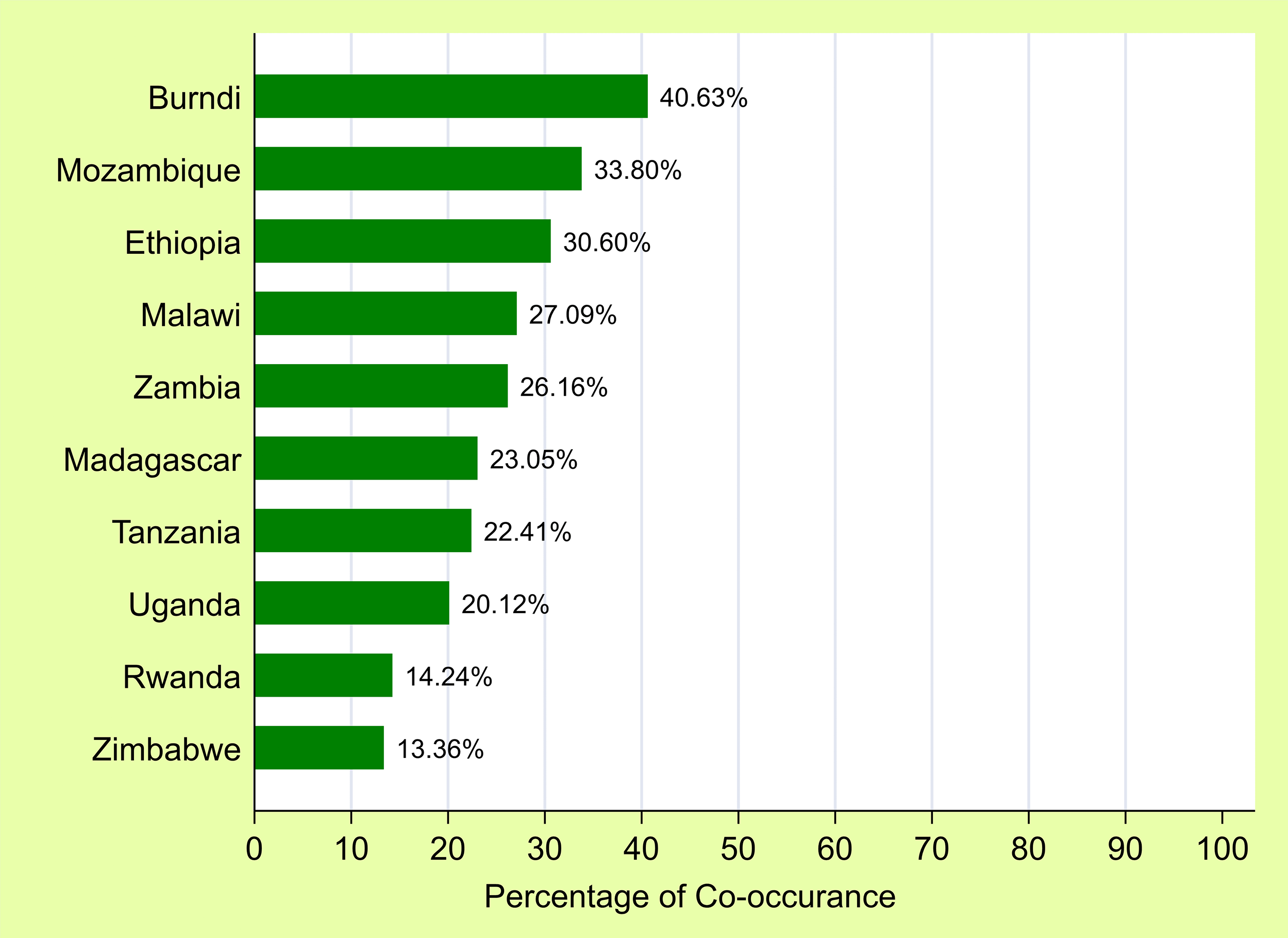

Graph shows spatial distribution and factors associated with co-occurrence of anemia and undernutrition among children aged 6–59 months in East Africa

A new study published in PLOS One reports that thousands of children aged 6–59 months in East Africa are battling both anemia and undernutrition at the same time.

Researchers warn that this double burden sharply raises the risk of illness, impaired cognitive development, and death.

Anemia remains one of the most widespread childhood health problems globally, affecting about 40% of children worldwide, with the highest rates in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In East Africa, the burden is even heavier, with estimates suggesting that nearly three in four children are anemic and national rates ranging between 35% and 80%.

The researchers identified clear geographic patterns of vulnerability.

“Clear hotspot areas were identified, particularly in northeast Ethiopia, northern and northwest Uganda, most of Burundi, northeast Tanzania, northern Zambia, central–southern Malawi, eastern Mozambique, and southern Madagascar,” the authors wrote.

The new research shows that 26% of children in the region experience both conditions simultaneously.

“Children living in hotspot clusters were 3–4 times more likely to experience the co-occurrence of anemia and undernutrition compared to children outside these clusters,” the authors wrote.

This finding underscores the need to prioritise resources in specific high-risk locations rather than relying solely on national averages that can mask deep regional inequalities, the authors say.

Maternal health emerged as a central driver of child outcomes.

“Maternal anemia is one of the strongest and most spatially consistent predictors of children experiencing both anemia and undernutrition, especially in parts of Ethiopia, Burundi, and Madagascar,” the authors added.

Children born to anemic mothers faced a much higher risk, pointing to an intergenerational cycle of poor nutrition. Tobacco use among mothers was also linked to low birth weight and restricted growth, particularly in parts of Tanzania and Mozambique.

Recent childhood illness also plays a major role. Diarrhea and fever were strongly associated with higher co-occurrence in several regions, highlighting the nutrition–infection cycle. Children who recently had a fever — often linked to malaria or other acute illnesses — were significantly more likely to suffer from both anemia and undernutrition.

Illness reduces appetite, interferes with nutrient absorption, and increases the body’s energy demands. This pattern was particularly strong in Burundi, Madagascar, and Mozambique, where malaria remains prevalent.

Poverty remains one of the strongest predictors of the dual burden. Households with limited income often struggle to access diverse diets, healthcare, and sanitation.

Age and gender patterns were also evident. Children between 12 and 23 months were at higher risk — a period when many transition from breastfeeding to family foods while facing increased exposure to infections.

Boys were slightly more vulnerable than girls. In contrast, children of overweight mothers appeared less likely to face the double burden, possibly reflecting better household food security. A lack of health insurance increased risk, pointing to barriers in accessing preventive and treatment services.