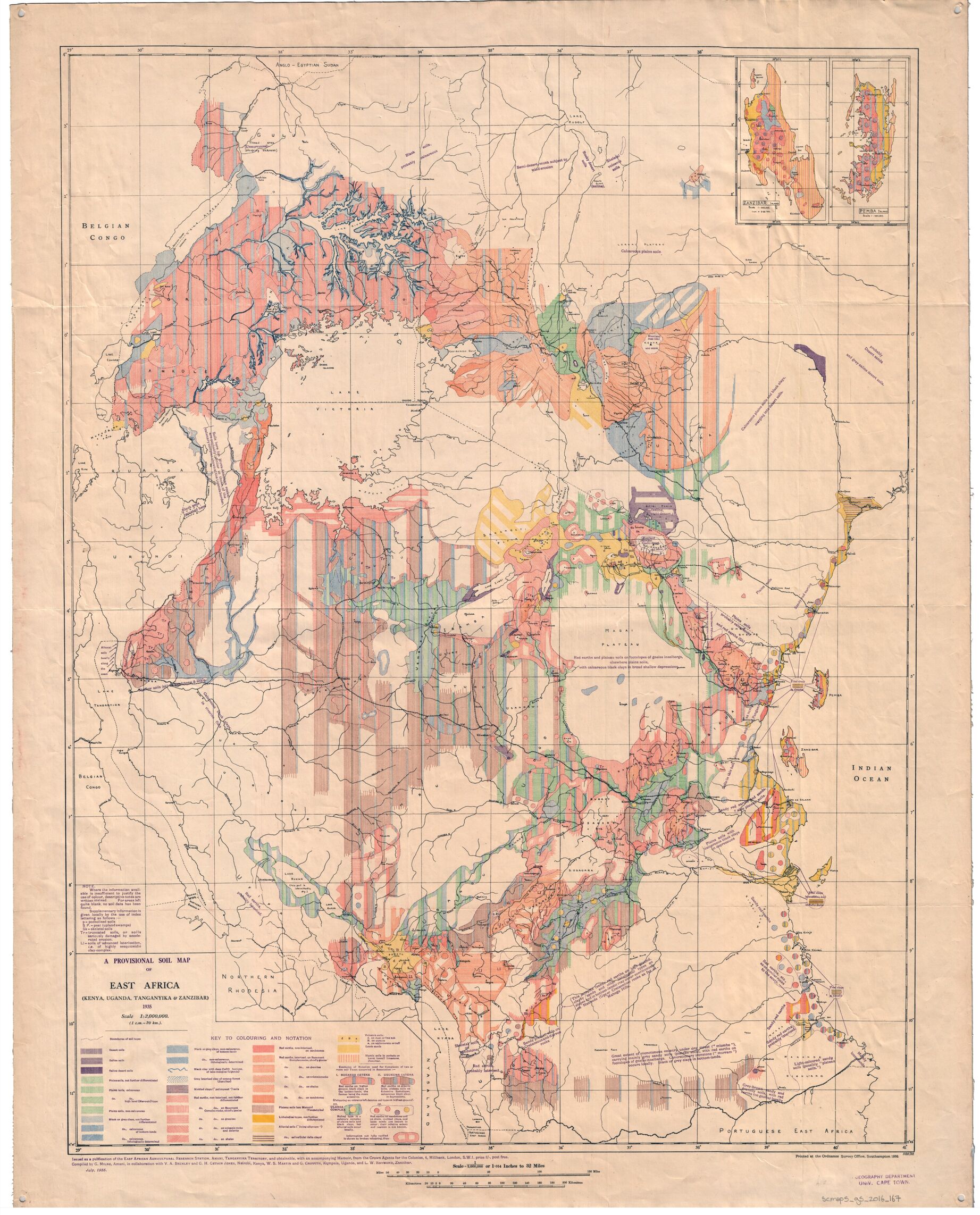

A major soil map created in 1936 to guide farming and land use in East Africa was ahead of its time scientifically, but it largely ignored African knowledge.

That is the conclusion of a new historical study published in European Journal of Soil Science, examining the Provisional Soil Map of East Africa (PSMEA), produced during British colonial rule in Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), and Zanzibar.

At the time, there was little organised information about African soils. The 1936 map brought together scattered research into one regional picture. According to the study, it was “an innovative contribution to soil mapping, summarising available information and communicating its incomplete and patchy distribution to the user.”

The scientists did something bold. They admitted where they did not have enough data. They showed gaps on the map instead of pretending the information was complete. That transparency was unusual for the time.

The research also challenges the idea that colonial scientists simply copied ideas from Europe or America. Soil scientists working in East Africa questioned some of the dominant global theories of the 1920s and 1930s. Instead of believing that climate alone determined soil types, they argued that many factors mattered — including the type of rock, the shape of the land, vegetation, and even human activity.

The study describes them as “a lively, robust and creative scientific community, by no means peripheral.”

Their ideas later became widely accepted in soil science. But the study also makes clear that the map was not politically neutral.

The researchers explain that soil surveys always reflect the priorities of those who fund them. “A soil survey therefore embeds both the assumptions about social and economic aspects of crop production and the power relations among different users of land which pertained in the political context of the time,” the study authors wrote.

In this case, the 1936 map was created under British colonial administration. It was meant to support agricultural planning and land management under colonial rule.

As a result, the biggest gap in the map was the absence of African voices. African farmers had deep knowledge of their soils, built over generations of farming. In some areas, colonial researchers relied heavily on local informants to understand land use. But that knowledge was rarely credited or formally included in the map.

“The voices of African cultivators or input from African soil knowledge are absent from the PSMEA,” the researchers say.

The 1936 soil map later influenced national and continental soil surveys. Some of its ideas — especially the concept of soils forming in patterns along slopes — are still used today.

Photo source