IMAGE CREDIT: CHATGPT

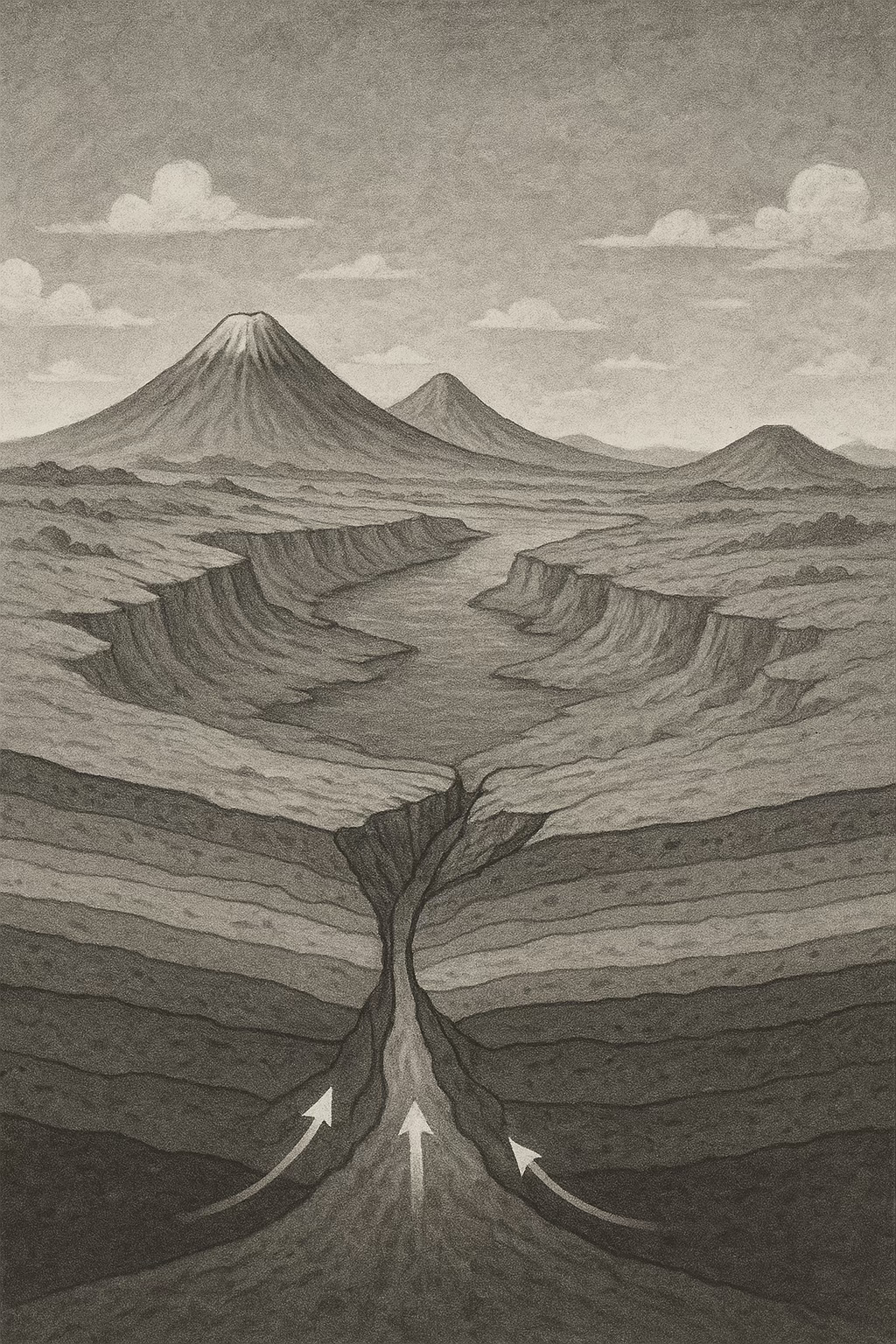

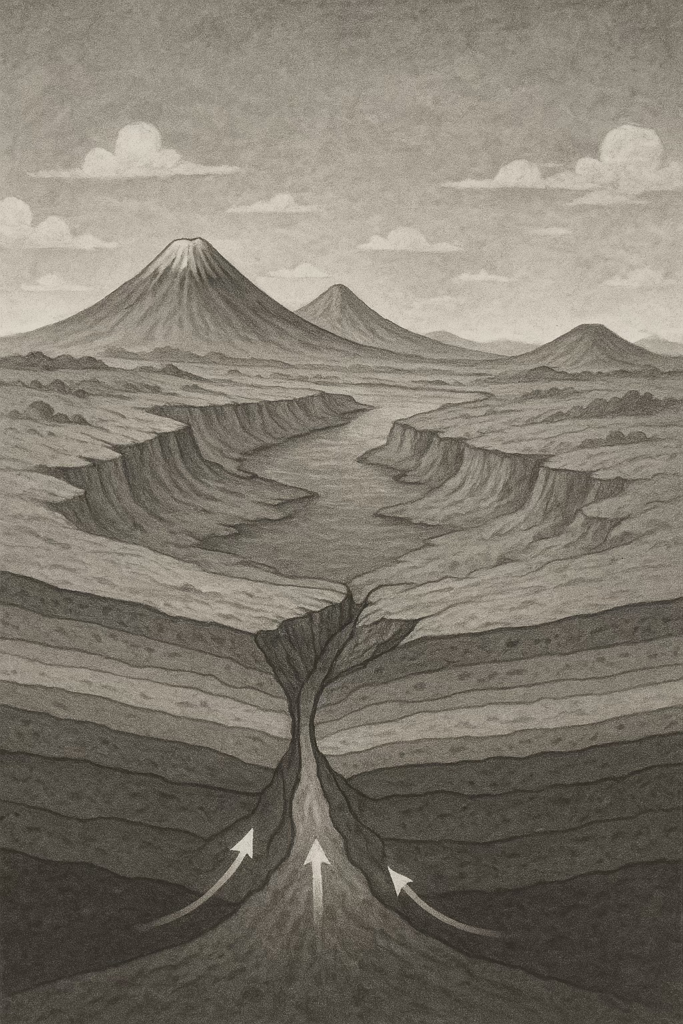

The East African Rift Valley is one of the world’s most striking natural landscapes, marked by dramatic escarpments, vast lakes, and towering mountains.

But it is also one of the most dramatic cracks on Earth. This long scar stretches from Ethiopia all the way south through Kenya, Tanzania, and beyond. Here is something you may not know: it’s more than just a valley, scientists say it’s the start of Africa splitting in two.

One day, millions of years from now, a whole new ocean could flood in. And this process began many millions of years ago.

A new scientific study published in Tectonics explains how, about 20 million years ago, the way volcanoes in East Africa were powered went through a major change. That turning point helps explain why the land looks and behaves the way it does today.

From heat below to cracks above

In the early days, the region’s volcanoes were mostly fueled by heat rising from deep inside the Earth. Imagine giant columns of hot rock slowly moving upward, like a lava lamp. These “mantle plumes” melted parts of the crust and created huge volcanic eruptions.

But then, about 20 million years ago, things shifted. Instead of volcanoes depending mainly on that deep heat, the land itself began to play the leading role. As the African continent stretched apart, the crust cracked like a breaking loaf of bread. Those cracks gave magma easy escape routes to the surface. In other words, the tearing of the land above became just as important as the heat from below.

Geologists can see this change in the lava left behind. The types of rocks show that stretching and splitting–what scientists call “rifting”–had taken over as the main force behind volcanism.

Why this matters today

This might sound like ancient history, but it’s not just a story of the distant past. For the millions of people living in the Rift Valley today, the process is still unfolding.

Volcanoes like Nyiragongo in Congo or Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania are part of this active system. They bring both benefits and dangers: rich volcanic soils that support farming, but also the risk of sudden eruptions.

Earthquakes, too, are part of the ongoing rift activity. By knowing when and how the rift switched from deep heat to crustal stretching, scientists can better understand today’s risks and prepare for what may come.

The landscapes shaped by this process–the long valleys, high cliffs, and deep lakes–are also vital to the region’s economy. They support agriculture, attract tourists, and even provide geothermal energy that powers homes and businesses.

There’s also a bigger story here. The East African Rift is one of the few places on Earth where we can watch, almost in real time, how a continent breaks apart. What began as deep heat has now become a slow but steady tearing of the land. Someday–not in our lifetimes, but perhaps in 50 million years–the crack could grow wide enough for the Red Sea to rush in and form a brand-new ocean.

The movement is slow, about the same speed your fingernails grow. But by tracing the shift that happened 20 million years ago, scientists can better understand how rifts evolve from cracks in the land to new oceans.

A reminder beneath our feet

For everyday people, the lesson is this: the ground beneath us is not still. It moves, shifts, and reshapes itself over time. The East African Rift shows that continents are alive with change, even if we can’t feel it day to day.

The new study connects the dots between ancient volcanic eruptions and the rift valleys and mountains we see now. It tells us that Africa’s journey from one landmass to two is already underway–slowly, silently, but surely.

It may take millions of years to see the full picture, but understanding this process helps us make sense of the earthquakes, eruptions, and landscapes shaping life in East Africa today.

PHOTO OF THE WEEK

“Cholera remains a serious threat in Chad” WHO says. WHO, Chad government and other partners out in the streets of one the cities sensitising people about cholera outbreak.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“There is very little air travel to this province and the journey from Kinshasa to Kasai can take multiple days by road during the rainy season,” International Medical Corps brief on a region where an ebola outbreak was declared this week in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

How Africa’s Hidden Streets Shape Poverty: A new study has mapped the physical layout of every neighborhood across sub-Saharan Africa, revealing how poor street access links directly to poverty. Using satellite images and digital maps, researchers showed that in many places, especially rural and peri-urban areas, homes are packed into blocks with few or no connecting roads.

These “invisible” areas often lack basic services like clean water, electricity, and health care — the daily realities of poverty. The team created an open online map, Million Neighborhoods Africa, so policymakers and communities can see exactly where the gaps are. The findings challenge the idea of slums versus non-slums, showing instead a spectrum of infrastructure access that affects development across the continent. [Reference, Nature]

Satellites and AI Reveal Ghana’s Pollution Hotspots: Air pollution is a growing health crisis in Ghana, but ground monitoring is scarce. A new study used NASA satellite data and machine learning to track tiny airborne particles, known as aerosols, from 2003 to 2019. The results show that southwestern Ghana has the highest pollution, fueled by forest emissions, illegal mining, and industry.

Major cities like Accra and Takoradi also stand out as hotspots, with levels above the national average due to traffic, industry, and offshore oil activity. The researchers found that a hybrid machine learning model gave the most reliable results. Their work provides a powerful new tool to map hidden pollution and guide policies to protect public health in regions lacking proper air-quality monitoring. [Reference, Plos Climate]

Unearthing West Africa’s Last Hunter-Gatherers: Researchers from the University of Geneva have uncovered a 9,000-year-old quartz knapping workshop and fireplace at the Ravin Blanc X site in Senegal, offering rare insights into West Africa’s last hunter-gatherers. The finds show skilled toolmaking, with standardized microliths in savannah regions contrasting with more opportunistic techniques in forest areas, suggesting cultural differences shaped by environment. Interdisciplinary analysis of charcoal, soils, and plant remains also revealed the climate and landscape of the time, shedding light on how these communities adapted during a period of major cultural and environmental change. [Reference, Plos One]

—END—