IMAGE CREDIT: CHATGPT

As we wound down November 2023, I traveled with Abdi Latif, the New York Times East Africa Bureau Chief, to report an article on the country dealing with one of its deadliest Ebola outbreaks. We interviewed dozens of people, including a man who had lost both his wife and son.

We also spoke with a survivor whose neighbors came and “tied ropes around our plot” to ensure she couldn’t leave the compound after her husband tested positive.

“I spent all day and night crying,” she said. Though her image had faded from my memory, it came rushing back when I saw a photo of her, surrounded by her children, published in the Times story. She was deeply emotional as she spoke to us.

More than two and a half years later, we get to understand the psychological trauma caused by the outbreak and the toll it has taken on so many others.

A new study published in PLOS Mental Health offers rare insight into the emotional toll of surviving Uganda’s 2022 Ebola outbreak–from the confusion at diagnosis to traumatic hospital stays and hostile reintegration into communities that once called them neighbors, friends, even family.

In the early days of the outbreak, many residents didn’t believe Ebola was real. Some private clinic workers–the first line of care for many rural Ugandans–actively undermined the official health response.

“They told me, ‘those are suspicious government plans; we can treat that fever; that is not Ebola,’” said one survivor, who initially avoided the main hospital and ended up moving from clinic to clinic while her symptoms worsened.

Her sister, who had similar symptoms, died after being moved from facility to facility, including a pastor’s home.

“She decided to go to the pastor’s place… she fell and fainted. They rushed her to [a clinic]… The doctor said that she had been injected with a drug which caused internal complications,” a survivor recounted.

According to the study, survivors described their time in hospital and isolation as one of intense emotional and psychological distress. Many spent weeks in open, unpartitioned wards where the suffering and death of fellow patients were inescapable.

“You would sleep beside someone, and the next morning, they are dead,” recalled one participant. Others spoke of the terror of waiting to die themselves: “I was just counting hours,” said another.The environment–meant for medical care–felt more like a place of constant mourning, with corpses sometimes left in the room for hours.

Even after surviving a deadly disease, many found no peace back home. Instead, they were met with whispers, avoidance, and outright cruelty.

“They used to see you… then they just turn and use another route,” said a survivor.“Someone greets me: ‘Ebola man, how are you?’” recalled another.

The stigma extended to survivors’ families. School administrators blocked children of survivors from attending class.

“When the school got to know that I was hospitalized… the children were discriminated against and stopped from going back to school,” said a survivor.

The study’s authors urge the Ugandan health system to rethink its outbreak response, as survivors’ testimonies highlight a glaring absence of mental health support, trauma-informed care, and community reintegration planning.

“EVD survivors’ experiences… are characterised with high levels of unattended psychological distress,” the authors state.

They recommend a “holistic person-centred approach to healthcare”–one that treats not only the body but also the mind and soul.

While it’s been just three years since the study participants survived Ebola in Uganda, the psychological trauma will likely linger for many more.

A 2024 study in BMJ Global Health looking at survivors of Sierra Leone’s 2014 Ebola outbreak found that nearly half still suffer from serious stress and trauma (like PTSD) even 6 to 8 years later. Some also struggle with depression and drug or alcohol use.

Uganda and Sierra Leone are not isolated cases. In a separate review of 21 scientific studies, researchers found that many Ebola survivors experience conditions like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. The paper concluded that 1 in 5 people who went through an Ebola outbreak were diagnosed with depression.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

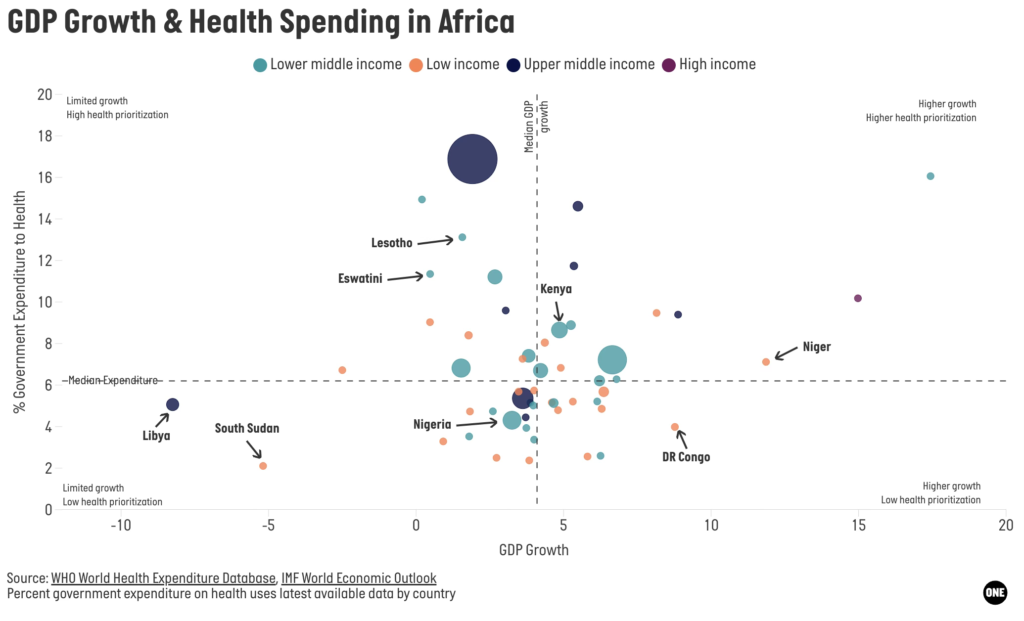

In Africa, economic growth has not translated into increased government spending on the health sector. The reckoning has come, especially now that Donald Trump dismantled USAID, which had been a major source of budgetary support for public health across the continent. Chart from a piece by One Data titled A Hinge Moment for Africa’s Health Security.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“We see so many natural disasters in the world, nearly every day and in so many countries, that are in part caused by the excesses of being human, with our lifestyle,” Pope Leo XVI. Picked from Katharine Hayhoe’s newsletter, read.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Link between climate change and violent crime: A study which examined crime patterns in South Africa found that while overall crime in South Africa dropped from 2017 to 2023, violent crime increased—especially in warmer seasons and in Gauteng Province. Heat, rain, and pollution were linked to more violence, with low income also a key factor. In 2021, South Africa had the highest murder rate globally. The cost of homicide reached $838 million, with climate factors responsible for 60% of it. The study suggests that improving the economy and reducing pollution can help reduce crime. [Reference, humanities and social science communications]

Trafficked Pangolins carry hidden disease risks: Pangolins are the most trafficked mammals in the world, and while concerns often focus on diseases like coronavirus, these animals also carry ticks that can spread serious illnesses to humans, livestock, and other wildlife. This study looked at ticks found on confiscated African pangolins and seized pangolin scales. Researchers collected 275 ticks and used both visual and genetic methods to identify them.

They found five different tick species, some of which are known to carry diseases like heartwater, African swine fever, and human relapsing fever. The study discovered new tick-host relationships and provided the first detailed data on ticks linked to trafficked pangolins. The findings show that illegal wildlife trade can also move harmful parasites across borders, highlighting the need for more research and better methods to identify and monitor these risks. [Reference, ScienceDirect]

Breast cancer hurts women’s productivity in Africa: Breast cancer is a major health issue for women worldwide, especially in Africa where it’s often diagnosed late and survival rates are lower. This study looked at 47 African countries over nearly 30 years and found that breast cancer significantly reduces women’s ability to contribute to the economy. Using health data like Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), researchers found that as the burden of breast cancer increases, labour productivity decreases—by up to 0.87% in the long term. The study highlights the urgent need for better cancer prevention, early diagnosis, proper treatment, and strong health systems in Africa to protect both women’s lives and their economic contribution to society. [Reference, Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics]

Elephants gesture with purpose, not by chance: The study “Investigating intentionality in elephant gestural communication” reveals that wild African elephants use gestures intentionally and with clear goals, such as seeking help or gaining attention. Elephants don’t gesture randomly; they often pause after gesturing to wait for a response, and if none comes, they repeat or change their gestures. They also tailor their gestures depending on who they are communicating with, showing flexibility similar to how humans adjust their speech. Researchers identified 79 different gestures used in various social contexts, highlighting a complex and meaningful communication system. This groundbreaking research shows that elephants possess advanced social intelligence and use deliberate, goal-directed gestures much like great apes and humans, demonstrating thoughtful and purposeful interaction among them. [Reference, Royal Society Open Science]

–END–