IMAGE CREDIT: CHATGPT

Do you ever feel a fever coming on? You take some antibiotics but the fever persists. That has happened to me several times.

What is worrying is that this is not just a personal problem, it is a continental trend. Medicines that once saved lives are no longer working the way they used to across Sub-Saharan Africa.

A study in ot yet peer reviewed, looking at results Communications Medicine, not yet peer reviewed, looking at results from 200 different research papers, found that many common and serious infections are becoming harder to treat. In fact, almost half of the infections studied did not respond to some of the main antibiotics doctors usually rely on.

“Antimicrobial resistance is a critical global health threat, with Sub-Saharan Africa disproportionately affected,” the authors wrote.

For years, these antibiotics have been trusted by doctors. They are used for chest infections, severe fevers, infections in newborn babies, and after surgeries. They work quickly, are widely available, and have been considered dependable. But now, they are losing their strength. Infections caused by some common germs are becoming especially difficult to treat, with treatment failure becoming increasingly common.

The problem is not only widespread, it is growing fast. Over the last two decades, the number of infections that no longer respond to these medicines has sharply increased. Before 2009, this was far less common. But between 2020 and 2024, the number of resistant infections nearly doubled and continues to rise each year.

“Temporal trends show an increase in resistance, with prevalence rising from 22.8% before 2009 to 42.0% in 2020–2024,” the researchers write.

The situation is worse in some places than others. East and West African countries show the highest numbers of difficult-to-treat infections, while Central Africa appears lower but that may simply be because fewer hospitals there have the equipment needed to test and record these problems properly.

Hospitals in rural areas also face bigger challenges. Many have limited staff, fewer laboratory facilities, and fewer medicine options. Doctors in these settings often have to guess which treatment to use, which can make resistance even worse over time.

Some of the most troubling cases occur in hospital units that care for newborn babies and for patients recovering from surgery. These patients are already vulnerable, and when the medicines used to protect them fail, the outcome can be tragic. Families may watch loved ones become sicker even after doctors have provided the best treatment available simply because the bacteria have changed enough to survive the medicines meant to kill them.

There are many causes behind this growing problem. In some areas, people can buy antibiotics without seeing a doctor, and sometimes medicines are taken incorrectly or stopped too early. Some hospitals lack proper hygiene systems, allowing infections to spread easily from one patient to another. And when the usual medicines fail, many facilities do not have access to stronger and more expensive alternatives.

This issue may be growing quietly, but its impact is loud and life-changing. It means infections last longer, hospitals struggle more, and families face higher medical bills. It also means more people may die from illnesses that used to be easily treated. The study warns that if nothing changes, the region may face a future where routine infections become life-threatening again.

Experts say there is still hope but only if strong action is taken. Countries will need better systems to track resistant infections, more training for doctors and nurses, and wider access to proper testing. Communities will need better education about when and how to use antibiotics safely. Most importantly, governments and global partners must work together before the situation becomes even harder to control.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

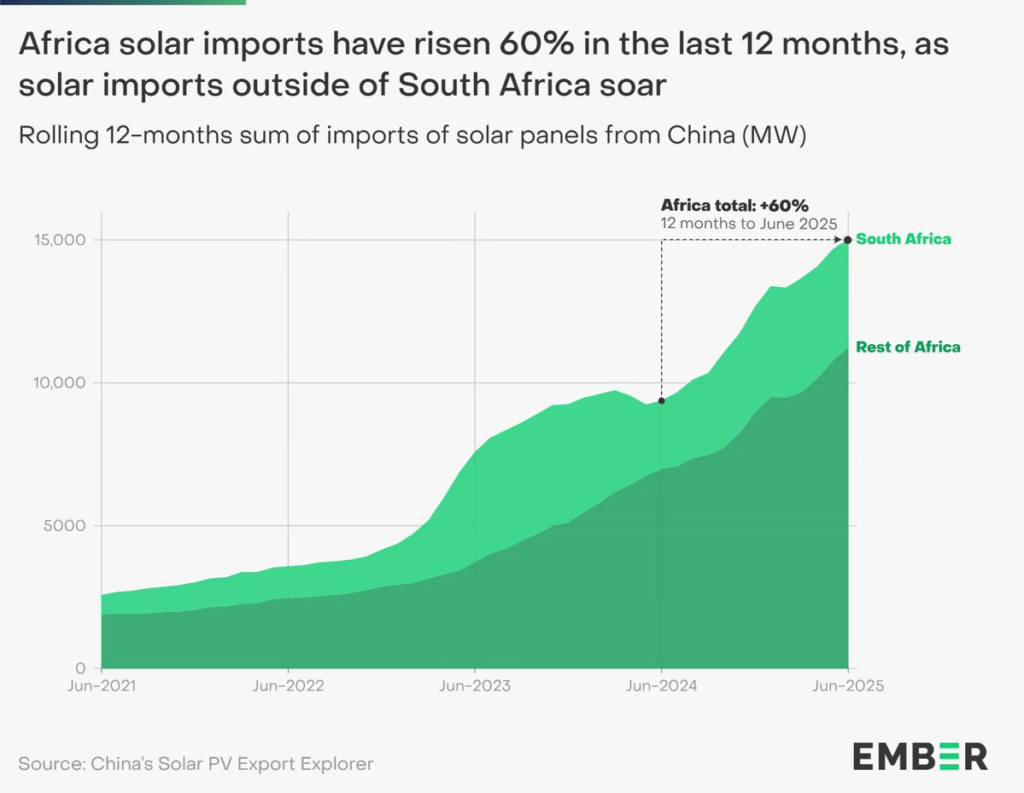

COP30 has just ended but Africa’s 60% surge in solar panel imports over the past year highlights momentum that can now be turned into faster, deeper progress on the continent’s clean energy transition.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

Africa’s strength is evident in the solutions we continue to build for our own research and health systems” Dr. Evelyn Gitau Chief Scientific Officer, SFA Foundation speaking at Africa Health and Development Annual Research Symposium last week in Nairobi.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

COVID Shots: Who Says Yes? A study found that the COVID-19 pandemic raised major questions about personal freedom and the right to accept or refuse vaccination. It examined how willing people in Sub-Saharan Africa were to get the COVID-19 vaccine, why some refused, and whether it is ethically acceptable to require a vaccine passport for international travel.

Researchers reviewed 40 studies from 23 African countries, involving over 107,000 people. About half (55%) were willing to be vaccinated, while one-third (35%) were hesitant. Eastern Africa had the highest acceptance rate. Hesitancy was mostly linked to misinformation, fear of side effects, distrust of authorities, and resistance to mandatory vaccine certificates. The study argues that future epidemics must consider the ethical implications of vaccine passports. [Reference, Science Direct]

Vaccines That Pay Off. A study which reviewed 41 articles on malaria, measles, and meningitis vaccines in Africa found that these vaccines are largely cost-effective. The cost per fully vaccinated child ranged from $1.60 for measles to $52 for malaria, and the health benefits, measured in years of healthy life gained, were generally worth the investment.

Introducing the malaria vaccine across 41 countries would cost about $185 million. While most vaccines provide good value compared to doing nothing, the malaria vaccine has a substantial budget impact. Overall, the study highlights that these vaccines offer significant health benefits and are mostly affordable for African countries, though careful planning is needed for funding. [Reference, Science Direct]

Understanding Burundi’s Mpox Spread: A study found that a new type of mpox virus started spreading in Burundi in 2024. Scientists looked at samples from almost 100 patients to see where the virus came from and how it was moving through the country. They discovered that the virus most likely came from the Democratic Republic of Congo and entered Burundi several times.

It may have already been in the country months before people realized it. The virus is mainly spreading from person to person, not from animals. Most cases were first seen in Bujumbura, but the infection later reached many other areas. The study shows that this mpox outbreak is ongoing in Burundi and needs attention to prevent further spread. [Reference, Communications Medicine]

—END—